Habitat: A Thousand Generations in Orbit preview: one man’s trash

You’ll want to steer, but you won’t be able to. Charles Cox doesn’t want you to. Endless space-based video games have taught gamers to manipulate analog sticks, a d-pad or a keyboard and mouse to steer all manner of spacecraft to precisely where they want them to go. Habitat: A Thousand Generations in Orbit doesn’t work that way. Physics have the wheel in 4gency’s strategy game, and they’ll be doing all of the steering. Cox hopes the approach will work.

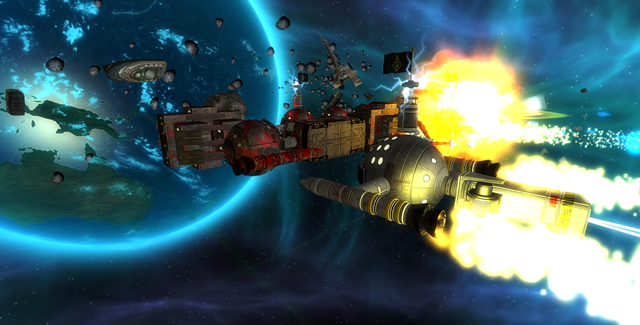

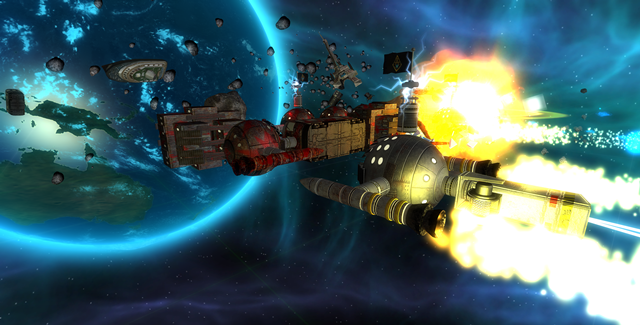

He showed up at PAX East last month with a playable demo of his ID@Xbox title. Actually, it was more a proof of concept than a proper demo — 4gency put together a playable outer space sandbox and filled it with junk, lots and lots of junk. There was no objective or end point to the demo. Instead, players were free to take the orbiting hunk of junk they started with (the titular habitat), weld whatever debris they pleased onto it and propel the thing through the space. Doing so is easier said than done.

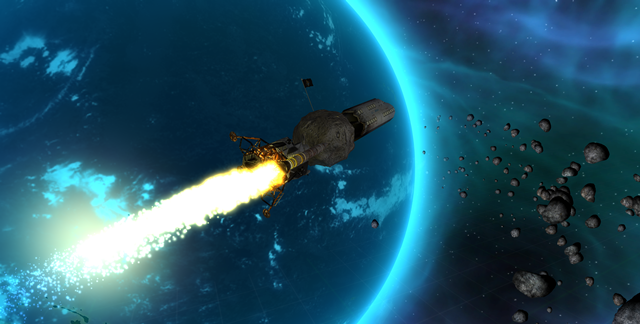

Your habitat is an unwieldy thing, as you might expect a floating mass of rock, rockets and pieces of famous landmarks to be. Movement is based on physics, so, again, there’s no steering controls for your rubble-craft. What you do have control over is the placement of rockets, the rockets you want to fire up at any given time and how much thrust you want from those rockets. A mistake at any of these three levels of propulsion oversight will lead to your habitat either careening off of other objects and being smashed to pieces or performing the spacecraft equivalent of doing donuts in a car parking lot. On top of that, players also have to manage electricity and oxygen levels, as some of one or the other is necessary for rocket power.

Taking control of a habitat, I immediately screw the entire thing up by unintentionally playing bumper cars with surrounding space debris. Crucial parts of the habitat are torn asunder and most of its inhabitants are killed. Cox restarts the demo and advises me on what to do. Even with his over-the-shoulder guidance, it’s next to impossible to not make a mistake. I continually place rockets in ill-advised locations, place one rocket where there should be a pair and apply improper amounts of thrust. There’s no shortage of space junk in the demo, and I crash into most of it during my play session.

Cox says that there’s “an art to this.” If so, Leonardo Da Vinci I am not. A successful go at things seems unfeasible, but then again, there are no conditions for success in the demo, so perhaps things will be different in the final game.

Exit strategy

What the demo does afford is the chance to build some truly wacky dwellings. It makes you wonder if perhaps George Taylor wouldn’t have been so upset about humanity blowing up the Statue of Liberty if he had just looked on the bright side: enterprising humans could use chunks of it to construct space abodes. In Habitat, you’ll have to manage humans as much as you manage the connected series of rocks and junk they call home.

Cox says that while you won’t get the same level of micromanagement in his game that can be found in the likes of the Civilization series or Spacebase DF-9, you will have to respect the value of human life and the research points gained from it in Habitat. “They generate research points that allow you to unlock things in a tech tree, and, above certain levels there are certain tiers,” he explains. “If you can get enough citizens you unlock additional engineers, so you can multitask more and more things. But you’ve got to keep the citizens alive to continue to get those points for research.”

Citizens and engineers are two distinctly different groups of people, and both are important in 4gency’s game. Engineers venture outside of habitats and are required for adding additional rockets and habitable modules onto your craft. They can propel themselves out to grab nearby space junk that the player wishes to cobble onto the dwelling. They’ll navigate their way right to anything in range, bring it back and start welding — unless the trajectory somehow changes. The slightest change in conditions can cause them to overshoot or undershoot the targeted junk, leaving them floating helplessly away into the vacuum of space. It’s important, then, to manage engineers wisely.

Citizens, on the other hand, can’t build up your craft. They reside inside of it and hope for safe passage and survival. To help ensure as much, they respond to situations and flow like a resource. They’re also the whole reason you’re building habitats.

“So the citizens really are your resources in their own way,” says Cox. “And of course, they’re the final — what’s the right way to say it? — they’re the final arbiter of whether or not you’re successful in this game. Because the story of Habitat is one of the survival of the human race. In the year 11000, we unleash nanomachines that are destroying the Earth — big mistake. And we can’t do anything to stop them! So the only thing we can do is throw everything up into orbit.

“And so human beings are coming up in regular intervals in colony ships, and you need to save as many as you can. As the career progresses, you’re going to get farther and farther away from Earth. Reinforcements of more citizens become much more rare until the final act when Earth is gone, and there are no more human beings coming at all. You need to find pieces of a faster-than-light (FTL) drive in this final sector that is scattered around by an alien race, attach them to your city and warp out with however many humans you have left to beat the game.”

The others

As on Earth, not all of the humans coming up into space want to be your friends. Some of them will be your enemies. Adversaries of the human and nanomachine variety will do everything they can to destroy your craft before you can assemble the FTL drive and escape into deep space with your surviving inhabitants. The playable build doesn’t feature either the nanomachines or other humans, so it’s impossible to say how Habitat levels will play out, but the basic idea is to build up your habitat, fill it with as many humans as possible, and keep them alive while ramming the business end of your dwelling into antagonistic habitats and smashing them to bits.

And then there’s that aforementioned alien race. Fortunately for aspiring post-nanomachine apocalypse survivors, Habitat doesn’t make the player fight a war of three fronts; the alien presence will likely only be in vestigial form.

“I don’t think we’re going to see much of the aliens except for what they left behind,” Cox states. Throughout the interview he gives the impression that he hasn’t quite figured it all out yet, but he sounds fairly confident that his game’s alien civilization is extinct. “The three main real character banks are your engineers and citizens, the engineers and citizens of this enemy habitat faction and the nanomachines themselves, because they will actually start to come off of Earth, and they’ll try to infect you. They’ll antagonize you, they’ll throw stuff at you as well as the enemy habitats.”

That means that it’s necessary to build up a habitat capable of space traversal as well as space combat. Players will be able to acquire weapons like grappling hooks that can be used to latch onto opposing crafts and rip them apart when thrust is properly applied. The chunks that are separated can then be used like any other piece of space debris to build out the player’s habitat with. There is no size limit currently in place for the domiciles — though there may eventually be practical limits due to memory constraints and “speed of light issues” — so it’s up to the player to decide what size dwelling is best.

“You’ll notice that, based on the junk types, some have additional points that are open up, and some are terminuses, where they only have one,” says Cox. “If you build all terminus points, then you’ve locked yourself out. But if you keep building and you keep opening up new points, sure, build all you want.”

Crashing without breaking

Cox has been busying himself building the game he wants to make. “This is a race into space where you really had to imagine a lot of this kind of stuff,” he says of his game’s premise. “I’ve seen a lot of games kind of be built up and games I’d like to play. I realized in February of last year this was the game I was going to build.”

It was then that he visited Washington D.C.’s Air and Space Museum and everything came together in his head. Cox speaks passionately of his visit to the museum with a huge smile on his face. The museum is full of all manner of aircraft, but it was a NASA Space Shuttle orbiter that inspired Cox to make Habitat. But there weren’t any instructions on how to turn inspiration into gameplay. The game designer points out that when he attended Space Camp, it had no classes on crashing space stations together.

“So this is really more creatively messing around with all the things that I’ve wanted to do, and play with this idea,” Cox says of his methodology. “This is the one that survived. This is the one that’s like, ‘No, no, I really think this is going to work.’ I’ve looked at it from every angle: ‘Well, what if this is going to break, that’s going to break?’ No, no. I think it’s going to work.”